In Turkey I am Beautiful was published in 2008 by Harper Collins. It’s a travel book about my time living and travelling in that country, including working in a carpet shop in Istanbul. It received excellent reviews. The Sydney Morning Herald called it “laugh out loud funny”, the Sun Herald named it one of the best travel books of all time, the Independent Weekly described me as the “funny gay nephew of Bill Bryson” and it was voted one of the ten best books of the year by ABC Radio National listeners and one of the 100 Favourite Books of All Time by a Borders poll. And I STILL didn’t make any money.

In Turkey I am Beautiful was published in 2008 by Harper Collins. It’s a travel book about my time living and travelling in that country, including working in a carpet shop in Istanbul. It received excellent reviews. The Sydney Morning Herald called it “laugh out loud funny”, the Sun Herald named it one of the best travel books of all time, the Independent Weekly described me as the “funny gay nephew of Bill Bryson” and it was voted one of the ten best books of the year by ABC Radio National listeners and one of the 100 Favourite Books of All Time by a Borders poll. And I STILL didn’t make any money.

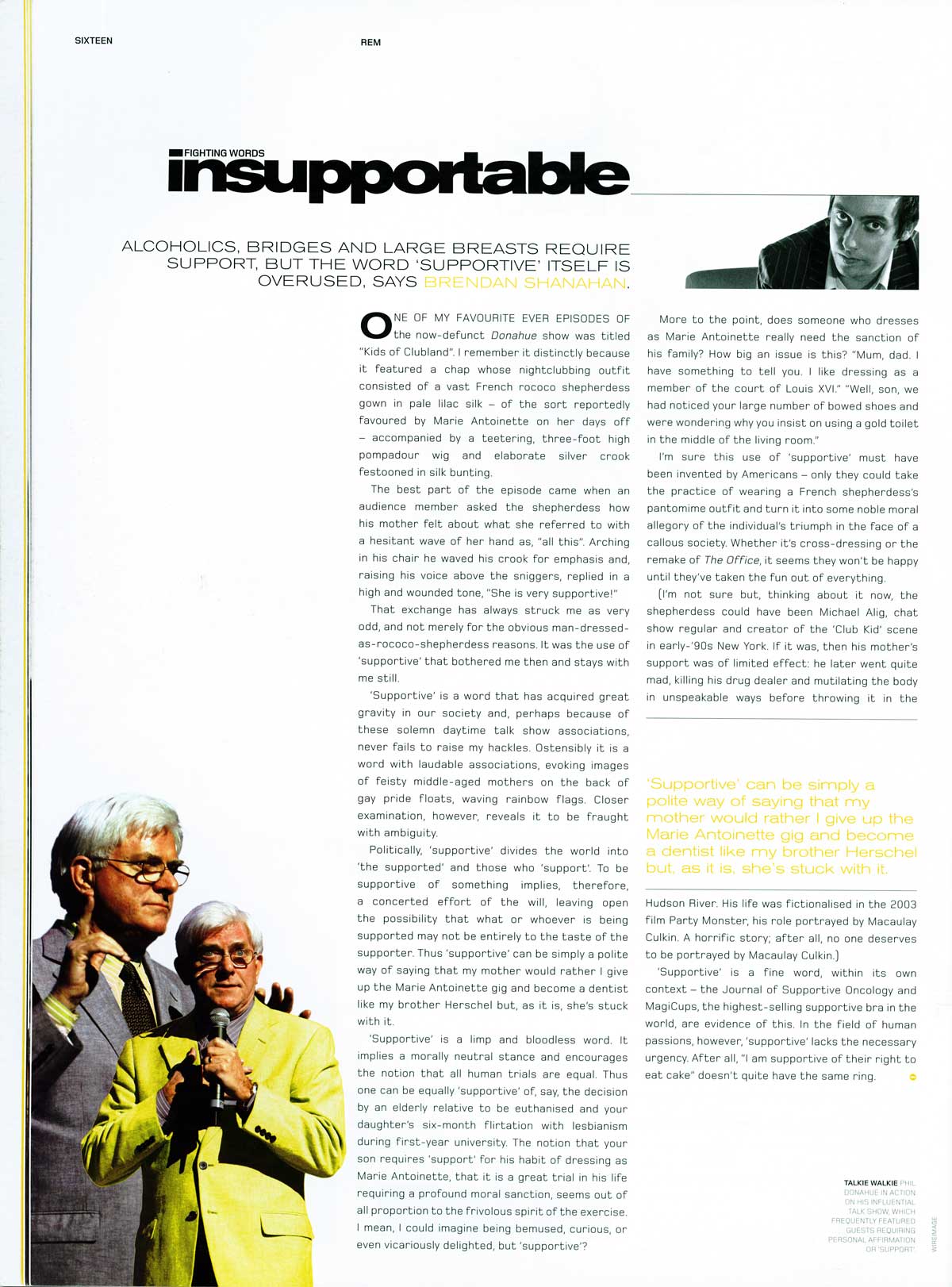

Istanbul’s waterfront, consisting of the Bosphorus, the channel where the Mediterranean and the Black Sea meet, and the Golden Horn,a branch stretching out to the northeast, is the city’s heart and saving grace. To the west is the European shore, to the east Asia, or Anatolia, a name used by the ancient Greeks, meaning “The Land of the Rising Sun”. The waterway that divides the two continents has been recorded and celebrated since the dawn of Western history. Through it the priestess Io waded after being turned into a cow by her lover Zeus, and Jason sailed on his search for the Golden Fleece. Recent archaeological evidence has even suggested that it may have been the origin of the Great Flood of the Bible when, seven thousand years ago, the Mediterranean broke through with cataclysmic force, creating the Bosphorus and filling the Black Sea.

Since its inception in the era of myth, the Bosphorus has been, arguably, the most fought-over, coveted and celebrated stretch of water in the world, a mantle of deep history it seems to wear lightly. Crossing the Galata Bridge on a fine day — with the bubbling lava domes of the mosques on the hilltops and the confetti of the painted houses landing on the dark hill of Pera, crowned by the elegant Galata Tower — is to feel your mood immediately lift. To look past the shoulders of the fishermen, and a handful of staunch-looking women, to see the silvery span of the suspension bridge linking Europe to Asia can make you smile involuntarily. It is a scene dazzling enough to make you forget about the hideous billboards, the fungal blooms of satellite dishes and the fact that the sad little fish seem to be swimming in something the colour of battery acid.

Istanbul is a Blanche DuBois city,best seen in low,artificial light. And much like the character in the Tennessee Williams play it has been the subject of some epic, and not entirely legal, fornications. Istanbul is the custodian of one of the most significant and beautiful waterways in the world, but it doesn’t seem especially grateful for the

privilege. Much of the shoreline has come to look like nothing more than a decaying monument to mismanagement and greed. The ferry terminal, for instance, is functional and lively but quarantined from the shopping districts, and major monuments such as the Egyptian Bazaar, by a four-lane motorway traversed only by a dank tunnel — stalls selling flannel shirts and squealing electronic toys — and a hideous pedestrian overpass hung with a billboard proclaiming, with incongruous cheerfulness, “Welcome to Istanbul”.

The situation is perhaps even more dismal on the other side of the bridge. Pera is one of the most historically significant districts of any city. Yet future archaeologists will surely scratch their heads in puzzlement when digging through two-and-a-half millennia of civilisation only to stumble on a layer beginning in the 1960s that seems to consist only of auto shops, hardware stores and dingy pedestrian tunnels selling handguns. (The guns fire only pellets, but, according to Hüseyin,it was an open secret that they could be easily bored out and converted to the real thing. Turkey has one of the highest rates of gun ownership in the world,a fact I was to learn first hand in spectacular style later in my travels.)

Further to the west, all the way to the Dolmabahçe Palace, the banks of the Bosphorus are blocked, almost entirely, by crumbling shipping terminals and rows of disused warehouses. In the middle of the decrepitude sits the new art museum, Istanbul Modern, like a gleaming sports car parked in the driveway of a burnt-out house. The outrages stretch across the city: from the dishevelled civic parody that is Taksim Square, to the boulevards of the Asian shore, where a handful of the grand nineteenth-century wooden mansions (called köskler) survive, like the last lonely specimens of some near- extinct creature, a reminder of the thousands that were burnt down across the city night-after-night for decades so that concrete tower blocks might be built in their place.

It is difficult to credit some of the things that have been done to Istanbul, and in my time there I often found myself wandering the streets muttering exasperated questions under my breath: how did this grand marble bank become a grand marble doss house for homeless glue-sniffers? Who was it that thought building a reflective glass trucking depot, trimmed in bright green aluminium, on the edge of a cliff with one of the most spectacular views in the city might be a good idea? Why this car park and why here? Sometimes in Istanbul it felt as if someone had handed a blank cheque to ugliness and said,“Go for it.”

Yet, try as they might, the combined forces of ineptitude, corruption and sheer barbarism could never completely kill the beauty of Istanbul. The poetry of the city is ancient and resilient; it comes from deep within the foundations and bubbles up to assert itself in the most unexpected ways. It was there in the arched back of a ginger cat picking its way through the accretions of filth in the alleys of Beyoglu; or the flashes of blue tile beneath the advertising hoardings stuck thoughtlessly across an Art Nouveau shopfront; or a corner of Byzantine foundation crowned by an abandoned wooden shack so rotten it seemed as if it had grown there, like a shell over a mollusc. It was a melancholy beauty, Istanbul being, fundamentally, a city of melancholy. And there were times when the deep sadness of the ruins,the alleys and the old advertising, peeling from the walls in rotten sheets of technicolour filo was almost overwhelming. I can think of no other big city in the world that makes me as pleasingly sad as Istanbul, sadness being to this city what health food and self-delusion are to LA. It was difficult to tell where this sensation came from,but it was there:in the faces of the people, sullen, doe-eyed and so reserved that if you laughed on the tram they would frown and press a chastising finger to their lips. It was in the torpor of the fat stray dogs lounging in the evening on the stone steps of the Galata Tower, their coats turned silver by the street lamp. Perhaps it came from the knowledge that almost all of that which came before had been swept away,strongly suggesting that all this, and you, too, would one day be gone.

Walking by the waterfront along the Golden Horn you pass the neighbourhood of Fener, once the centre of Istanbul’s Greek community. It is here that the Orthodox Patriarchate, the Vatican of the Greek Orthodox world, still clings to life against all odds, the last vestiges of the citizens of Byzantium. Now the handful of churches are virtually empty or abandoned and the beautiful stone and wood houses with their latticed windows and carved lintels are falling apart. Other structures in the area have been reclaimed as blacksmiths or auto workshops.

In spite of or, perhaps, because of its ghosts and its decrepitude, Fener is one of my favourite districts of Istanbul. Much of it is on a high hill, offering views over the water, and the houses, although shabby, are among the most beautiful and untouched in the city. Most of the Greeks who once lived in these homes, who built the churches and the spectacular high school clinging to a precipitous hill, were driven from Istanbul in 1955 after a series of vicious riots when they were forced to “return”to a country where many were regarded as Turks and treated as outcasts. (Much of the violence committed during the riots — including forced circumcisions — was performed by paid gangs who had been shipped in by the members of the ruling Democratic Party with the apparent sanction of the then Prime Minister, Adnan Menderes. He was later deposed after one of Turkey’s seasonal military coups, exiled to an island off the coast of Istanbul and, eventually, hanged. Even in living memory Istanbul’s history reads like a Biblical epic.) Over the next twenty years, these expulsions were periodically repeated until the Greeks of Istanbul had been reduced to a fragile, aging population of only a few thousand, outnumbered even at their own church services by curious onlookers and superstitious Muslims keen to absorb the benefits of an older magic.

Today much of Fener is a fundamentalist neighbourhood,full of women shrouded in their çarsaf,some bold enough to ignore the law prohibiting full-face covering to walk the streets draped from head to toe, like black spectres with plastic shopping bags. Scenes like these have made indigenous Istanbullular sentimental for a time when the city was a multi-ethnic stew in which almost half the population was of non-Turkish ethnicity. In those days, along with the Greeks, Istanbul had large Armenian, Arab, Italian and Jewish populations, many of the latter the descendants of refugees from the Spanish pogroms of the fifteenth century who still speak a medieval Spanish dialect. (Next to Fener is Balat, a major Jewish area where some synagogues still survive. Istanbul’s Jewish community is no longer as big as it was, although much larger than the Greek, and many are wealthy and influential.)

This dimly remembered era of multiculturalism,when you could get a beer on the streets and bacon was on the menu, has become sentimentalised and romanticised by those who feel they no longer recognise the city they once owned. Poor rural immigrants have changed the face of Istanbul, a fact frequently repeated to me by the native citizens of the city in tones of barely repressed despair. When I suggested to a friend of mine who was looking to buy a flat that Fener seemed a good and relatively cheap area, she laughed in my face. “I could never live there! The women would hit me for not wearing a headscarf. If I have a party they call the police straight away. They would make my life a misery because I don’t pray. Fuck them!” Even in Istanbul in the twenty-first century the laws of God still trumped those of economics.

Istanbul is now one of the twenty biggest cities in the world. Since the 1980s its population has quadrupled to an official figure of over eleven million, but with estimates of the unofficial population ranging between twelve and sixteen million. Whatever the real number it is,essentially,worthless because every day there are at least five hundred new arrivals, the labour force of the booming Turkish economy.A large proportion of Istanbul’s new immigrants live to the west beyond the old city walls, the boundary of old Constantinople, in vast, unknowable suburbs which, pictured in a satellite photo, look like a burst mutant cell.The lucky ones may have a room in one of the endless, numbing rows of concrete tower blocks that seem to cover at least half the country. Many, however, live in the jerry-built slums known as gecekondular.

Turkish is a marvellous, not to mention deceptively literal language (more on that later), and gecekondu is one of my favourite words in it. “Gece”means night and “kondu”means, roughly, “to land”. Thus a gecekondu is “that which has landed at night”, so-called because those who build them are exploiting a legal loophole allowing any structure built at night and still standing in the morning, undetected by the powers-that-be, to remain. And so, every night in Istanbul, much to the horror of many of its ancestral residents, more and more gecekondular are created and the city grows bigger and bigger, in secret and under the cover of darkness.

Wealthy, urban Turks often spoke to me of the gecekondu as Dantean visions of urban despair and chaos: badlands to be avoided at all costs and irrefutable evidence of the inevitable decline of their city at the hands of rural rednecks. One girl who had researched the structures for her university course was to tell me in whispered horror that she had actually seen houses where the kitchen and bathroom were joined together.The gecekondular are, in fact, well kept, occasionally well built and often, as urban slums go, and compared to those I have seen in places such as Southeast Asia, rather pleasant. The streets were generally clean and only the newest structures conformed to the slum prototype: rough wooden frame, plastic sheeting or plywood for walls, a tin roof weighed down with old tyres. Most, however, were made of bricks, stolen from building or demolition sites, tiled roofs were not uncommon and a large number were completely indistinguishable from legitimate apartment blocks. Many had a little patch of garden, well-stocked with peppers, melons and tomatoes, and walking through the winding streets, past the chicken coops and wailing portable tape players blasting out arabesk, the music of the slums, I was frequently delighted by details that made these districts much more charming than their equivalents in many parts of the world: blooms of red geraniums in old white-painted vegetable tins sitting by the doorway; a rusted chimney poking from the side of a house, bent like an “s”, as in a children’s drawing of a witch’s house; doors and window frames painted in bright blue and pink; one house all in rainbow stripes. I rarely felt threatened.

It would, of course, be absurd to claim that the gecekondular were some sort of proletarian utopia. A large number of these buildings have no services — water, electricity or sewage — and almost all are overcrowded. In addition, they remain prone to flood, fire, collapse due to poor construction and, deadliest of all, earthquakes. (When a massive earthquake hit the satellite city of Izmit in 1999,most of the official fifteen thousand who died there and in Istanbul were living in gecekondular, especially the apartment buildings which crumbled like sandcastles.) Tensions run high in these conditions. Many rely on illegal power, hijacked from the grid, but, over the years, in a pattern of slum politics repeating itself throughout the world, swathes of gecekondular have become official or, at least, semi-official and attract most of the basic services common to any city. The politics of the gecekondu are complicated; during election times the ruling party used to hand out title deeds to the occupants of the land on which they were built, guaranteeing votes. Furthermore, most are still controlled by various branches of the all-powerful Istanbul mafia who “sell”the land to the new arrivals,control many of the utilities and,of course, the heroin refineries that process the estimated 80 per cent of the drug that ends up on the streets of Europe.

Reading the statistics and the gloomy newspaper reports, it was tempting to get bogged down in a vision of Istanbul as a crumbling dystopia: a fading, moth-eaten duchess, forced to sell off her estate, piece-by-piece,to an encroaching suburban ugliness. In fact, contrary to the persistent complaints of seemingly all its citizens, the city has handled its massive population growth comparatively well and is one of the most pleasant and sophisticated metropolises in any developing nation. Istanbul was a city of melancholy but also one of unexpected poetry and tenderness. I felt it whenever I encountered one of the gloomy but friendly street dogs that roamed the dark alleys of the old city, their ear tags signifying they had been immunised against rabies, the locals not having the heart to shoot them. Or the time I was sitting in a café in a corner of a fashionable inner-city area full of antique stores selling late-modern furniture, only to look up from my table to see a man carefully tending a patch of high, shaggy corn that he grew on a traffic island.

Istanbul was sad but never grim: in the windows of the dire hardware stores on the waterfront, the nuts and bolts were displayed in neat rows of short fluted glasses, like a robot’s dessert. And I remember how excited I had felt while driving on a drab stretch of road to an unremarkable shopping district to pass under a Roman aqueduct straddling the highway, the road fitting perfectly the width of the archways, as if it had been foreseen fifteen hundred years earlier.

I crossed back across the Galata Bridge, oblivious to the advertising hoardings, the car parks and the traffic. Descending into the concrete tunnel which would take me back in the direction of the shop, I passed the men screaming the prices of shoes and rows of crazed bellydancer dolls, their stocky plastic arms issuing frantic karate chops to unfamiliar music, then emerged into the fading daylight. There was a slight chill in the air. I began to head past the Yeni Mosque, a huge structure opposite the ferry terminal, where men sat by a row of taps, washing their feet before prayers. In the square in front,old women and little boys were feeding stale bread to pigeons. The birds gathered to eat until they became a single shimmering grey mass, like wet stone, a child’s sudden ambush sending them scattering skyward to give the illusion of evaporating masonry.

Istanbul: I said the name out loud. Is-tan-bul: I just liked the sound. Oh, Istanbul — it was good to be back.