Commissioned at the end of 2000 while I was still a rock music critic for the Sunday Telegraph, this biography of Rose Hancock Porteous – maid-turned-millionaire housewife superstar, Filipino-Australian icon and suspected murderess – was pulped only days after its initial printing in 2002. Although the sting still tickles, “Poodles on Prozac or the Incredibly Strange True Story of Rose Hancock Porteous” did create some “buzz” in the Australian literary world, later identified as a hive of European wasps in the air conditioning at Random House. Until such time as it can see the light of day, please enjoy this extract…

Commissioned at the end of 2000 while I was still a rock music critic for the Sunday Telegraph, this biography of Rose Hancock Porteous – maid-turned-millionaire housewife superstar, Filipino-Australian icon and suspected murderess – was pulped only days after its initial printing in 2002. Although the sting still tickles, “Poodles on Prozac or the Incredibly Strange True Story of Rose Hancock Porteous” did create some “buzz” in the Australian literary world, later identified as a hive of European wasps in the air conditioning at Random House. Until such time as it can see the light of day, please enjoy this extract…

CHAPTER 5

At eight am on December 27th, I packed up my things in the back of Graham’s slightly beaten-up Volvo and once again climbed the ascent to Prix d’Amour, this time to penetrate its gates and to meet its owner and architect. As we entered the driveway the gates opened for us shakily to reveal the full bulk of the building. As the car crunched over the gravel of the circular drive Rose’s assistant Trevor could be seen from behind glass doors under the portico. He fiddled with the doors for a moment before emerging to usher me in with a motion of harried distraction. He had gained weight since the photo in the book had been taken and was now dressed in a shabby pair of shorts and a sweaty T-shirt. The casualness stuck an unexpected note in the mise en scene of Prix d’Amour.

The vestibule was not so much decorated as stacked, rather like a rug merchant’s closing down sale at the local town hall in which everything must go at simply crazy low, low prices. Tulle cascaded down the windows in translucent ripples and oversized pots held large feathers, stretched symmetrically towards a ceiling which, like an up-ended shoe box, was too tall for the space.

From this extravagant airlock, like a flea jumping off the dog and realising the true scope of the universe, I stepped into, or rather was sucked into, the vortex of Prix d’Amour’s ballroom. In a vast sweep to my left, the area (“room” seems hopelessly insufficient) swung out before me in an extravagant CinemaScope tableaux of textural promiscuity. The interior of the building shimmered: green fought with gold, which fought with silver, which fought with glass, which fought with alabaster, which fought with silk, which fought with marble, which fought with hand-carved wooden curlicues, which fought amongst themselves, which fought with the sheer Baroque extravagance of it all, which won. The whole thing was about the size of a tennis court and would have required the eyes of a bird or a bug to comprehend at once. To my right a pair of plaster sphinxes, each supporting a glass tabletop, guarded an unopened double door. A series of green, mock-marble pillars with gilded plinths in the centre formed a room within a room to encase an immense dining table over which loomed the chandelier I had seen on the front of the cookbook. A second chandelier, literally tonnes of Waterford crystal, hung over my head. I watched carefully as it turned slowly, threatening imminent and spectacular collapse.

Trevor led me past the green pillars, past a white marble staircase which swept up to my left, conch-like, into a funnel of light, and across a vast sea of parquetry before depositing me at the other end of the ballroom. He disappeared through a door hidden by a floating wall laden with golden mirrors, clocks and candlesticks. As I waited I idly inspected a shelf of assorted knick-knacks. Presumptuously plucking a golden cherub from its shelf, I was surprised to find it nothing more than plaster with a “Made in China” sticker on the base. I replaced it as though it had been made of gold and stared down the length of the ballroom through the forest of pillars. At the eastern end of the space a large Victorian oil painting dominated the wall. Surrounded by an extravagant gilded frame it was a coy Leda and the Swan in a mannered horizontal composition. A reclining nude dominated the foreground with a wisp of cloth draped over her tiny crotch. A shifty-looking swan lurked in the bushes behind her. As a work of art it was unremarkable except for the fact that it appeared in the home of Rose, Australia’s very own Leda. The swan could almost have been Lang in one of his white safari suits.

Directly behind me, beside the door into which Trevor had vanished, hung a full-length oil painting of Rose in a red dress. Next to it was a more aesthetically impressive Judith and Holofernes. A tough, mannish Judith with a decent tan and vaguely Middle-Eastern features stood in the green tint of a studio light, looking off into the distance with grim determination. A tuft of hair in her left hand implied the unfortunate general. Again the choice of subject matter seemed remarkably apt. An exotic beauty seducing an older man and then doing away with him in the dead of night… Somewhere else in Perth, somewhere across the river, smoke curled out of Gina Rinehart’s ears at the continual reproach of the big middle finger on the hill, but the two paintings went on staring at one another across the glinting wastes of the ballroom, smirking at their private joke.

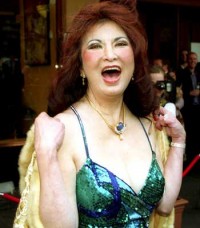

The joke ended abruptly. As I stood and stared at Judith with my back-pack on, Rose skitted across the parquetry from another hidden door clad in a bathrobe, a cream silk night gown and a pair of masseur sandals. I hadn’t expected her to arrive on a pair of rollerskates clad in a flaming red Givenchy frock, but nor had I expected this. She grinned and flung her arms wide open. “Hello Brendan!” She landed delicately on my shoulders, soft as a flying squirrel, and kissed my cheek. I held her in turn but she was so small she seemed to disappear under the grip of my hands into the folds of her night dress. I retreated, afraid of breaking her. Rose has long limbs and boyish hips; her hair was down and she was not wearing make-up. As her face moved closer it revealed a surprising flawlessness; she looked much prettier in life than she did on television. I reciprocated her greetings and told her she looked fabulous for fifty-two. “I lost weight!” she exclaimed. “I didn’t eat anything but avocado smoothies last month!”

We stared at one another a little awkwardly for a moment until she noticed my quick glance at her feet.

“I’m recovering from bad circulation”, she said, pointing to her reddened feet with their sore-looking toes. “That’s why I’m wearing these shoes”.

“You’re so tiny Rose,” I said, by way of breaking the tension. “I feel like I could pick you up and snap you!” She giggled, grasped her dressing gown and did a little turn for me. Unexpectedly, her hands were red and chafed from work and her fingers appeared almost blue. “Oh Brendan, are you hungry?” I was fine, but Rose continued her greetings and her motherings, saying how happy she was that I could come and expounding upon all the marvellous adventures we were to have. All the while her limbs sprang open like traps, her rhythm broken by an unnerving habit of scratching her rump like a rabbit.

The freshness of Rose’s face was in terrible contrast to the state of her limbs and chest: above her breasts ran a network of scratches like red spiderweb; the soft skin of her arms was scratched and bruised and there was what looked like a track mark scar on the inside of her arm. As though oblivious to their condition, her limbs continued to unfold and her happy yammering dared me to keep up. Suddenly, she spun on her heel and lifted the back of her night-dress. A large gauze bandage splashed with iodine was clinging to one buttock. “I was in the garden,” she exclaimed, and her brown eyes grew wide, “when a balaclava man came in. I tried to run.” She gestured running. “But he conked me on the head.” She gestured conking. “And I sorta… fell doooown.” She gestured falling. “And I tried to run away, but he stabbed me with some kind of implement.” Her stabbing hand twisted into the flesh and then pointed to her backside. “I’m lucky to be alive! And the police say that they don’t know how they got in!”

An unpleasant yellow crept across the bandage as I stared in dumb disbelief. The story had shades of an earlier report she had made to the police about three masked men who had tied her up in her kitchen in the middle of the night, taken topless photos of her, and then threatened to blackmail her by placing them on the Internet. I was disturbed by the stories and I was suddenly struck by an image, a painting by Magritte: a room full of sinister bowler hated men stand over the corpse of a naked woman, blood trailing from her mouth.

I forgot the image as Rose continued her stories and her enquiries after my health. Her energy was infectious but it was also relentless, leaving little room for easy interaction. She was nervous. We both were. Rose took me by the hand and we made our way upstairs in a small, white lift smelling strongly of its studded-leather lining. We were very close. Searching for conversation, I said, “Rose I can’t believe how young you look. Are you sure you haven’t had a facelift?”

“Nooo. I haven’t had a facelift!” she was vehement.

“Really?” I was teasing by now.

“Brendan! You don’t believe me?” she was genuinely hurt.

“No, I believe you Rose, it’s just that you look so young!” She grinned and silence followed. There was a large bruise behind her left ear. I considered asking her about it, but thought better and just laughed. She seemed very pleased as we stepped out of the lift.

Her hands, although reddened, were soft when she touched my arm, but her nails were chipped and brittle. “Look here!” she said, extending her right forefinger. It was gnarled and swollen with the nail a tiny triangle in the centre of the bed. “They almost had to chop that off.” She gestured chopping on the offending finger. Suddenly she made a rapid and disconcerting scratching gesture against the inside of her arm. “They were giving me an injection,” she mimed an injection, “but I have no veins, so they had to go in here.” She revealed a messy scar on the inside of her pale wrist. “And they went into my artery. But they didn’t know it was my artery, and I almost died! They were close to amputation.” Her arms exploded once more.

We walked down a lengthy corridor, past the gigantic marble staircase encased in windows and sweeping down to the ballroom. The walls around us were plastered in paintings in a vaguely art Nouveau Style. Rose noticed my interest.

“Rene Gruau was a fashion artist for all the big houses. Like Chanel, Balenciaga, Schiaparelli.” She said the names with love. “I have many of his works. He painted some just for me.” At his best Gruau seemed an incisive graphic artist with a keen sense of composition – at his worst, a tacky stylist. Images from both ends of the quality spectrum surrounded us. “People think I’m vain, Brendan. You see these paintings here?” She pointed to two images of dark-haired women in red dresses. “The tour buses told people they were portraits of me just because they have black hair! They say that I put the curtains up at night so that people can see me! It’s unbelievable!”

I agreed that it was most unfair. That said, the walls of Prix d’Amour are covered in pictures of Rose. At the end of corridor, a gigantic painting of her in a rainbow ball-gown standing in the ballroom by the Steinway grand faced us, looming larger as we approached. A soft focus portrait of Rose in a smart Chanel suit and stiff pose smiled down benevolently from the top of the stairs like a dictator on the wall of an African post office. There were glamour photographs from her “return to modelling” in the early ‘90s: hair a mass of teased seaweed, lips split invitingly. More natural looking modelling test shots from her European years in the ‘70s and a sprightly young Rose in black and white graduating from university. There were even a few where her posing was undercut by a sense of spontaneity, and Rose, the brilliant bad girl, emerged from behind the facade of Rose, the vampish tramp.

Rose showed me to my room beneath the central portico. It had an ensuite bathroom and its own little balcony from which to wave at tourists. I was informed that the room was once known as the ‘Ceaucescu Suite’ (and, before that, the ‘Bjelke-Petersen Suite’) in honour of Lang’s old business buddy Nicolae, who used to stay there before he was executed one Christmas Day by his unhappy citizens. Bathed in a colour veering perilously close to aqua, the room was very pleasant, if a little reminiscent of the seal tank at an aquarium. I left my things by the vast canopied bed and we started off down the corridor to continue the tour of the house as we chatted – or rather, as Rose talked and I listened.

She started on the subject of Gina. “Brendan, I tell you, I would rather work with a drug addict or an alcoholic, because at least they have their lucid moments.” Her sandals flopped as she walked. “What I am dealing with here, Brendan, is an institution case.” I laughed. She stopped, turned and raised a finger. “What killed Langley was the realisation that Gina – had – stitched – him – up.” She spoke haltingly, placing emphasis on every word for effect, and poked the air around me. “These people they are paying! We have evidence that they are being payed. They are just embittered former employees.” She waved her arms dismissively. “One of them, she was hanging out at the casino and giving blow jobs in the cubicles for ten dollars.” I presumed she was talking about one of the witnesses to be called for the inquest but it was difficult to keep up with Rose because the topics of her conversation seemed to veer from one to the other with little regard for chronology or logic: complaints about a Perth jeweler blended into tales about the old days in the Philippines, which in turn ran into a story about Lang, which then became a story about who-knew-what. Sometimes funny, sometimes baffling, and always without a pause, Rose’s stream-of-consciousness followed me on our tour – as though her conversation were a separate entity from Rose herself.

I interrupted. “How did you get those scratches Rose?”

She stopped and turned. “These are all skin rashes from the weather.” She whined in mock pain. “In Malaysia everything is air-conditioned and then you go out on the streets and everything is so humid.”

We reached the end of the corridor, walked past the lift, and entered Rose’s study. To the left was the enormous arched window that led on to a rectangular balcony. “This is a copy of the one in the White House,” she announced. “And here is my desk where I do all my work. You know I designed all of Rose’s Way to a Man’s Heart myself? Just on my computer.” I inspected her CD collection: a series of ‘Greatest Hits of the ‘60s’ compilations with a bit of Strauss thrown in. She pointed out the window at the house next door. “Langley loved me so much he didn’t want to see a crease on my forehead. I was like a little baby. He put me there.” She mimed a baby’s playpen. “And the toys he would put inside. And if I got fed up with the toys he would replace it with another toy.” By “toys” I presumed Rose meant her boutiques, multi-million-dollar jewellery and the properties, like the neighbouring house which, or so she claimed, she would buy and sell over the dinner table. Walking across to the far end of the study, Rose curled up foetally on a large couch and announced, “Langley would hold me like this, you know, just like a cat.” Then, with gentle hand gestures: “And he’d do this – just pat my bot-tom. Like a poochie.”

She sprang up. “Willie was very important to me because he built my self-esteem back up again, whereas Hancock crushed it. Lang practically crushed my self-esteem because he wanted me to be totally dependent on him.” She emphasised this with crushing gestures. “From a very free-spirited person – for me home was sleeping, going to bed – and then suddenly you’re limited because you are the wife of a very powerful man, you are a possession. I never thought of myself as a possession until three years after Langley’s death and I was always saying ‘Why? Why? Why?’ And then somebody said to me, I think it was the lawyer, ‘Because you are Langley’s most prized possession.’ And then I realised, ‘Oh, I am a possession, not an ordinary maid or a partner.’” Rose admits she boiled over and often blew her top at Lang, but she also maintains that her pouting and tantrums were all part of her appeal. “I would say, ‘How dare you patronise me you fool. Do you think you are God’s gift to Australia?’ And that’s what kept Hancock going with me, because I didn’t cow-tow. And I meant it.”

The tantrums, the craziness, the mood swings, the shopping trips to Paris, the life-size replica mannequins of herself, far from being the behaviour that drove him to an early grave, were all part of Rose’s appeal. The man, I suspect, had never had so much fun in all his life.

“I don’t know how to thank you Rose,” I said. “I was going to get you a present but I couldn’t decide what to get a woman who has everything.” Rose turned and raised a finger. “Brendan, really, you don’t have to worry, but, if you want to give me a gift, then I might get you to write my eulogy.” She paused. “Because I might be needing one soon.” With a solemn nod of the head she floated out of the room.

We headed to the rear of the house and entered Rose’s personal beauty salon; it was bright pink and tubular, like an old-fashioned parlour for middle-aged women. She pointed to the barber’s chair in which she used to dye Lang’s hair.

“He used to come out with a black line across the top of his forehead and I’d say, ‘Well, waddaya expect? I’m no hairdresser.’”

A glass cabinet with glass shelves consumed the entire wall to my right. Stretching seven feet high and bedecked with Rose’s perfume collection, what seemed a hundred bottles of valuable scents glittered in the mirrored backing in a disco-light display of cut crystal. She removed one of her favourites. “It’s very expensive. In the car if I smoke then I always have a bottle of perfume and then I spray the perfume.” She pumped the bottle and walked into the scented mist, then bent down to spray the rump of her poodle.

Behind me a huge mirror, rimmed with lights, like a dressing room scene from a 1940s Hollywood movie, ran the entire length of the wall and reflected the dull light that filtered through the drawn shade.

Pushing through a landing, again surrounded by photographs of Rose, we made our way to her bedroom, an immense space dominated by a tremendous bed with a sea-shell shaped head and a homely patchwork cover. Rose was complaining about a former friend who had been quoted in a women’s magazine in an article entitled, “I Was Her Slave”. “She pictured the house as having sexual orgies here and all-this and all-that. I have a writ against ACP [Australian Consolidated Press] and after the inquest I’m going to serve it. She lived in that house – this is how ungrateful some people are – she lived in that house.” She pointed in the direction of the neighbours. “That house is currently being rented by the Japanese for almost $700 a week. I rented it to them for $220. And the cheques bounced all the time. And she used to come in here and get food because the husband is a drunkard. But you know, unfortunately, I would not pass judgement on her…”

The monologue moved on to the threat of menopause or, rather, her imperviousness to it. Taking a hard left, we walked into her wardrobe. It was three times the size of my bedroom in Sydney. A full spectrum of Chanel suits marched into the distance. “Did you know that Blackwell voted me one of the world’s best dressed women?” she asked, lifting a Balestra suit for me to inspect.

“No…” I didn’t know who Blackwell was, but it prompted Rose to a lengthy monologue about her taste in clothes and her contempt for those who had accused her of vulgarity.

“Well most Australians have very conservative taste.” I said by way of consolation, and felt ashamed. Did I think Rose had good taste? No, but my dislike of those who thought they knew what good taste was outweighed any objections I had to her own sense of style. She bent down. “You see these shoes,” she said, lifting a smart pair of Charles Jourdan loafers. “Every time someone comes in the house these shoes are Dettoled. I wash the soles.”

“Oh no,” I said. “Should I have washed my shoes?”

“No, no.” She paused and looked a little distracted. “This floor needs a wash anyway.” A door from her closet led us to her enormous bathroom, the floor of which was lined with newspaper for her poodles to poo on. In one corner sat a sunken tub the size of a small apartment where her husband had once found her being baptised by a group of door-to-door Christians.

She began to describe her daily routine. “First thing at five-thirty in the morning I lock myself in – usually Willie is asleep – and I wash the whole bathroom myself.” Rose produced the cleaning implements she used to clean it before proudly presenting me with another set of implements with which to scrub the first. I was dumbfounded.

“Rose why do you do this? You could afford to employ someone.”

This prompted a lengthy monologue about poorly trained and over-paid domestic staff and, besides, she had been raised that way. “It’s a habit my mother taught me. She always said, ‘Who knows, you might be poor one day and can no longer afford domestic help.’” And it’s not all domestic help that will happily wash a dog in Pine O Cleen. “I used to do it every day but the vet said it was bad for them,” she explained as we headed back out to her study. By way of example she lifted a nervous grey poodle onto a chair, bandaged her finger in a Kleenex and began to drill into its tiny arse with determined little twists. “I grew up with my mother saying dogs were dirty,” she explained, peering up from her position under its tail. Once finished, she rose and scooped the dog into her chest with one hand, and, with the other, deposited the tissue stained with a little brown circle of poo into the waste paper bin.

Tick, tick, ticking their way around the disinfected floors on little disinfected nails were Rose’s three poodles, Dennis, Lulu and Linus, known collectively as “The Poochies”.

“Dennis is the most neurotic. He’s my favourite,” she said, nuzzling the grey, snarling cheek of the freshly wiped creature. Lulu was black and fluffy and the size of a ten-cent piece, while Linus was white and old and the most placid of the three. Linus had been rescued from neglect by Rose, and now his only danger was being killed by kindness, for in addition to keeping their dirty little sphincters scrubbed with lemon-fresh disinfectant, Rose has left them a quarter of a million bucks in her will. Yet the extravagances lavished upon them didn’t seem to have made them particularly relaxed. Every time I approached they would either shiver in fright or snap at my knees and fingers.

“They were, for a while, on Valium,” she said, sinking deeper into Dennis’ fur. “I did not realise, these creatures do suffer. There was a time Lulu was so affected by my health – I fainted one day – well, Lulu sits on my stomach and cries like a child. So she went through a period of anti-depressant. Just one course.” She paused, looked up and cuddled Dennis. “I love Dennis more than I love Joanna,” Joanna being her only daughter. She grinned sneakily and then snuggled back into the angora hide of her poodle.

With Dennis’ frantic legs scissoring behind us, we went back out through the salon and down a flight of wooden stairs. A garish image of the Sacred Heart hung over our heads. A monologue about her uterus morphed into me. “The children nowadays have no ambition in life.” She looked at me intensely. “I admire you Brendan.” Her head gave little shakes, as though under internal pressure. “You could very well be sitting out there on social welfare, on the beach, but you’re working.” She moved onto how moved she was by the loyalty Patrick Kuan had shown her at Christmas. Turning right through the ‘white’ kitchen (the second kitchen, reserved for functions), we walked down a dark corridor towards the maids’ quarters (a remnant of a time when Rose had live-in help) and turned right into the “hat room”.

Rose unlocked the door and led me in. I gazed at the floor-to-ceiling hats that lined the walls in every conceivable sculptural configuration, arranged according to colour for instant selection. Feathers, beads, silk, sequins, fake flowers and every other possible knick-knack and frou-frou lay on the shelves in a frenzy of appliqués, embroideries and rosettes. It looked like the aftermath of the Great Bedazzler Massacre of 1986. Rose did a little modeling with some of her favourites but soon her conversation turned again to the inquest and a psychic called Tara whom she had once hired for a reading and was now apparently due to give evidence against her.

I had seen Tara on the TV news. She had emerged from an earlier court case in dark sunglasses and swaddled from head to toe in a green, hooded velvet muumuu. Turning to the cameras, she had announced mysteriously, “My gift comes from the Holy Spirit.” Rose turned to me, “One of her allegations was that I sexually abused her!” The feathers on her head jiggled. “My God! She is as fat as this.” She stretched her arms out and I laughed with the memory of Tara and her spooky muumuu. “I tell you Brendan, I would rather be raped by ten men, I don’t care if they look like monkeys, but never with a woman.” I exploded with laughter. “Brendan you look at me now. I tell you what: I can seduce any man if I want to. That’s what Willie says. When it comes to being a seductress, I’ll admit to that. It may be an asset; it may be a liability but I have a classy way of seduction. I dunno, Willie says I seduced him. I didn’t intend to. But unfortunately in the Philippines they always call me ‘Sexy Rose’….” She continued as she replaced the hats. Rose locked the room as we left, and then went to get changed for an expedition.

Underneath Prix d’Amour is a garage that you reach in the white leather lift (“I designed this for Langley so that he could come straight up from the garage and into the study”). Connected to the garage is a cellar where, Rose told me, a thousand bottles of $1200-a-bottle champagne once went off after being left unopened for too long. Now it was full of crates of Sprite and various bottles of liquor. In the garage were two Mercedes and a beautiful turbo Bentley worth either a quarter or a half a million dollars depending on who is claiming its ownership. I prayed we would take the Bentley. Unfortunately, our mission to drop off a roll of film required only the lesser regality of a Mercedes.

Rose, Dennis and I piled into the car and swept out to the local mall.

From under the house we zoomed, the light hit the car as we sprang forth into the clean Perth air; and now we were a silver flash. At the end of the circular drive the gates opened as if by magic. The Thunderbirds were go and the gawkers could only stare. I turned and scratched Dennis’ head; his claws dug into my crotch. Eat my dust, hicks! I was with Rose.

We rolled down the street. A slow pace but with screeching turns. Rose was a terrible driver but, hey, that was okay, she was the lady of the manor and when a living legend almost turns into you at the exit of the mall car park, potentially crumpling the bonnet of your blue, standard-issue society matron BMW, all you can do is look angry and squint until you realise who it is, and then you just look confused and wave them around because, whether you like it or not, the power of Rose’s solid mojo melts your head like a birthday candle.

I stayed in the car to mind the poochies while Rose deposited the film. When she returned I went to buy some tapes. Inside the mall I was a schmuck in shorts, sweating with the rest of them. But returning to the cool of the car I became the guy with Rose, and people craned their necks to cop a look at my skinny legs.

Back to Prix d’Amour, back through the gates, back through the staring parade of slack-jawed tourists, under the ground. The lights in the garage flashed on as the garage door sprang open. We zoomed up the lift, the garden appearing through a window, drowning the cabin with light as we floated to the top, and, for just a moment, I was drowning in whiteness. The doors opened to the glitz of the ballroom. The light beamed out from the lift in a solid shaft, refracting across the textures of the ornament, running little electric tracings around the edges of the clocks, the candlesticks and the glassware figurines with the Lalique stickers on them, commanding them to life with a flick of the Mad Scientist’s switch. We floated into the ballroom and clopped across the parquetry. The delivery of film should always be so.